Jean-Christophe Rufin's report on Mozambique liquified natural gas (LNG) project's involvement in humanitarian and human rights issues explores a series of sensitive issues that have damaged relations between local communities, the government, and the companies involved in the LNG project on the Afungi peninsula, Palma district, since 2013.

In particular, issues inherited from Anadarko's management of Mozambique LNG have driven a series of conflicts within the populations affected by the LNG project. The contested award of land use rights known as DUAT, to Anadarko, the mismanagement of compensation and slow progress on resettlement, and consents obtained in problematic ways have made for a stressful decade for the people of the Palma district. The March 2021 attack on the town further delayed a conclusion to the difficult and problematic process of resettlement.

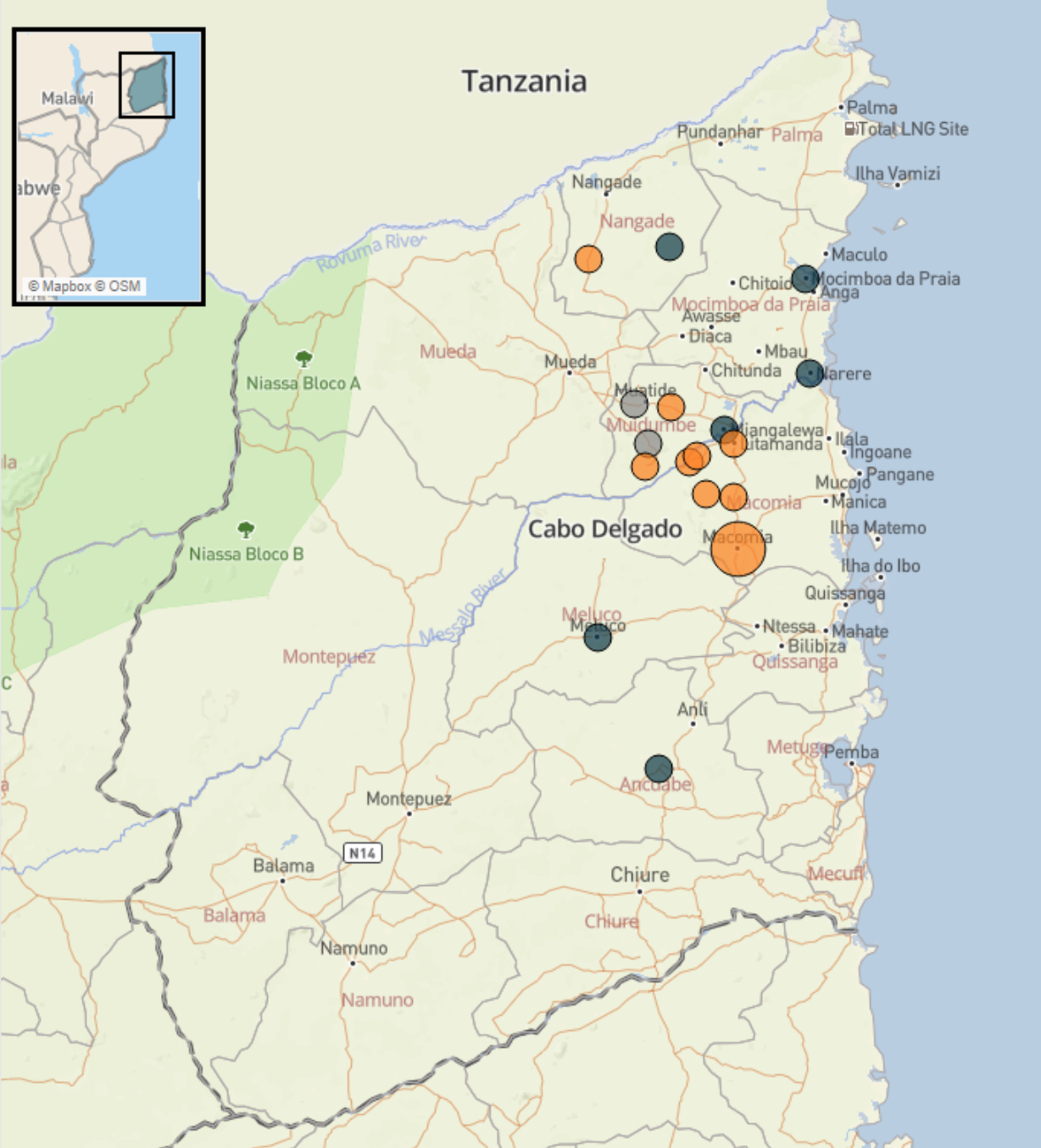

This piece is from the Cabo Ligado Monthly: May 2023

Many of the issues stem from the allegedly illegal award by the Mozambican government of the DUAT for an area of 7,000 hectares on the Afungi peninsula, in favor of Anadarko, without the consent of the communities. Legally, the transfer of the DUAT from the communities, held by them on the basis of customary laws, should have been a long and complex process, requiring community consultations, studies, and the issuing of an environmental license. But the government bypassed the customary laws and allocated the site in 2015 to Rovuma Basin LNG Land (RBLL), a special purpose company established by Anadarko and Mozambique’s national oil company, Empresa Moçambicana de Hidrocarbonetos. An independent audit by civil society organizations that year concluded that this process was illegal.

Moreover, neither RBLL nor Anadarko justified at the time the need for such an extensive area of land, which would have provided a buffer zone around the project – suggesting that Anadarko did not intend to establish any relationship with the population surrounding the project.

One question raised by Rufin is why part of the significant area of the DUAT not to be used for the LNG plant is not now allocated to the local communities, either for the relocation of their housing or even for the development of agriculture.

The allocation of the DUAT to Anadarko led to another issue identified by the Rufin report. The 733 households to be relocated from the extensive DUAT through the resettlement process had no land to establish their new homes and farms. Instead, they were placed in other communities, generating inter-community conflicts, and thereby pitting resettled people against their hosts. For example, those being resettled were given houses of modern construction; this contrasted with the precarious material of the houses of the host communities. Rufin suggests the creation of the same housing conditions for both populations, something that is in line with the demands of the communities at the time of the public consultations.

Anadarko and the government also failed to identify alternative agricultural land for the resettled communities, turning instead to the village of Senga to secure about 150 hectares which were already used for cultivation to compensate for the farms of the resettled people. However, this is a short-term solution, since as the population grows, the pressure on the existing land will increase. TotalEnergies and the government will have to find a long-term solution to this.

Rufin also addressed the problematic way in which the government and Anadarko obtained consent from the local communities. For example, some families were allegedly coerced into signing documents proving that an inventory of their property had been made, under the threat of not receiving compensation. In fact, in many cases, such inventories were never carried out. Rufin also agreed with some civil society organizations that community consultations had been conducted with a lack of transparency and access to information, and a lack of clarity about the procedures involved in the process, rendering the community consultations mere administrative and bureaucratic formalities. When communities are not properly informed and lack adequate knowledge, they are not in a position to express their concerns and priorities in an informed manner.

The negotiation phase between the government and the company on one side, and the communities on the other, was a long and difficult process that lasted about six years until the resettlement of the populations finally began in 2019. Of the 733 families, around 161 were resettled, but the process was suspended after Total's ‘force majeure,’ leaving some 572 families still to be resettled. As the inventory process had already been done, the populations were not allowed to build or change the conditions of their houses and were not even allowed to work on their farms, generating a state of uncertainty among them. Also lacking in clarity are the populations who used to live in coastal areas in the DUAT area. The population of Milamba, whose main activity is fishing, was displaced inland, along with their boats, instead of being relocated to other coastal areas.

Rufin's report on the issue of resettlement and compensation for communities seems to reflect the pressing concerns of the people affected by the Mozambique LNG project, and overlaps with issues raised by civil society organizations throughout the resettlement process. Having mapped out the underlying problems, the key issue now will be how TotalEnergies addresses these challenges.

Rufin's recommendations already point some ways forward, although some of them are vague. Updating of consent, inventories, prompt payment of compensation, and compensation of land for agriculture all deserve more attention. The fishing populations that used to reside in the coastal area of Milamba have already been resettled to areas far from the coast. TotalEnergies will have to find a sustainable mechanism for these communities, which have historically been entirely dependent on fishing.

Some of the issues raised by Rufin in his report are a direct criticism of the way the government has handled the process, where business interests have taken precedence over communities. TotalEnergies’ approach in Palma will also be dictated by the company’s economic interests. But criticism of the resettlement and compensation process led by Anadarko and the government of Mozambique may give TotalEnergies more room and autonomy in leading its development strategy. The success of this strategy will depend on how it responds to Rufin's recommendations.