Good morning, after a busy week for Zitamar News. There have been developments in the unexpectedly fascinating pigeon pea export saga, and in the never-ending hidden debts saga; we have also published deep dives into Mozambique’s potential for clean energy.

Need an office in Maputo? Check out MMO:

Would you too like to reach our audience of almost 4,000 Mozambique investors and stakeholders? Contact subscriptions@zitamar.com

We started the week by noting that Mozambique’s repayments on its sovereign eurobond, which started life as the Ematum ‘tuna bond’, will rise sharply. Last week’s repayment was the last one at the annual rate of $45m; from here on out, the bill is $81m per year.

But it’s not all bad news for Mozambique. After President Nyusi’s victory earlier in the month, winning immunity in the London court case, the UK’s Supreme Court ruled this week that Mozambique has the right to sue Privinvest, the shipbuilding group that it alleges was the architect of the deals which bankrupted the country. Mozambican media ended the week by reporting that Mozambique is seeking damages of $10 billion — an extraordinary figure, but one that nevertheless could be justified.

There was good news too for pigeon pea producers, after the artificial restrictions on exports to India, apparently put in place as a sweetheart deal for a politically-linked company, were lifted. Zitamar’s reporting revealed high level connections with a Frelimo member of parliament who owns a company caught up in the murky dealings.

Next week there are dates for the diary for readers watching developments in the gas sector. The Mozambique Gas and Energy Summit takes place in Maputo on Wednesday and Thursday. By coincidence, TotalEnergies is due to hold an investor day on Wednesday, updating on its future strategy. It could be an opportunity to provide an update on their plans for Mozambique LNG.

Of course, as we never tire of saying, gas is not the only game in town, even in the energy space. This week we published a report on the state of graphite mining in Mozambique, and its prospects for the coming years:

And gave the same treatment to the prospects for the production of ‘green hydrogen’ in Mozambique too:

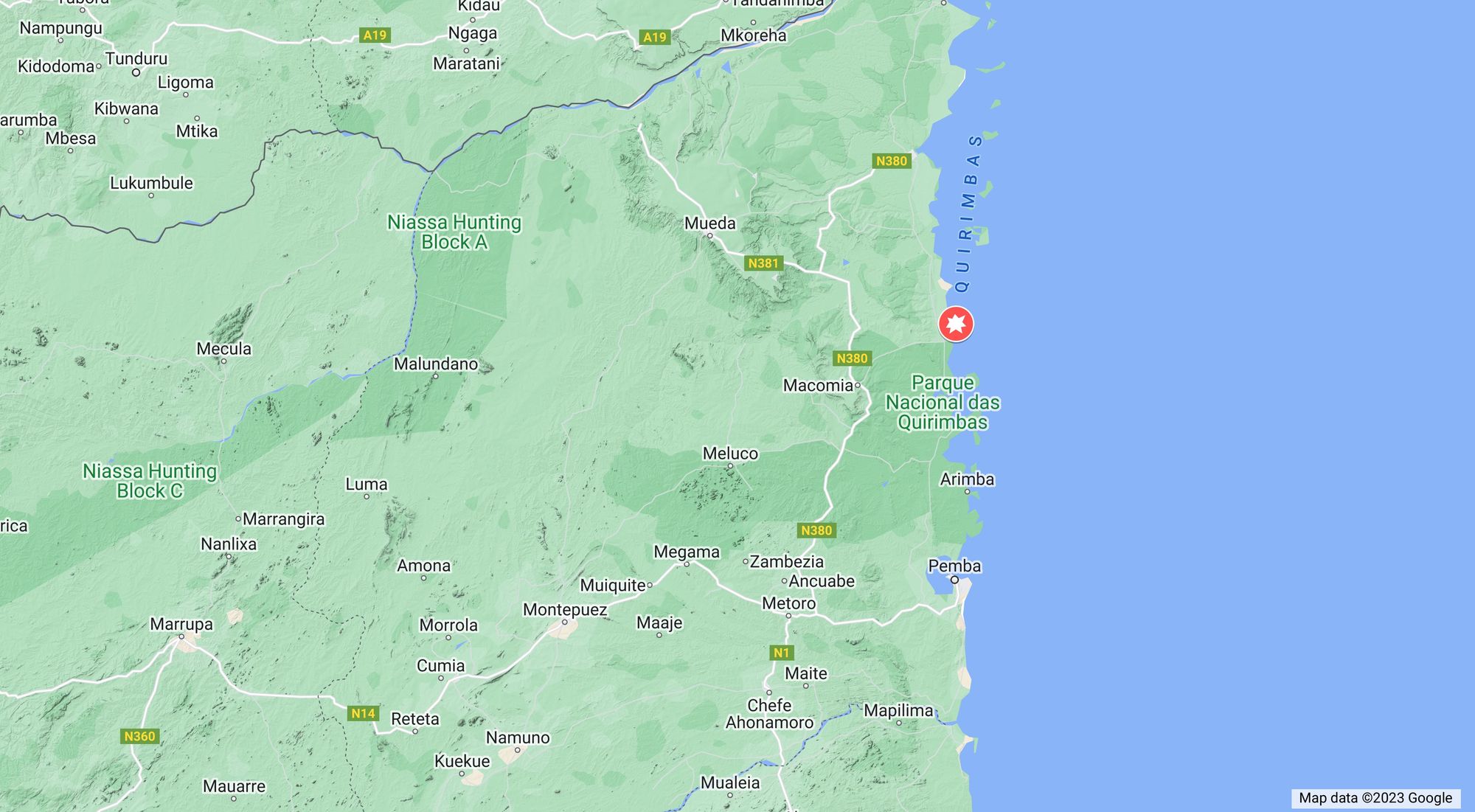

And finally, with the conflict in Cabo Delgado continuing at a reduced tempo, the updates from Cabo Ligado are now fortnightly. The latest one, however, is a reminder that even if the government now seems to have the upper hand, the conflict there will be very difficult to bring to a definitive end.

Don’t forget that Zitamar continues to bring breaking news from the conflict, in between the fortnightly updates; those stories are always free to read:

Below is a sample of the insights we’ve sent to paying subscribers throughout the week. To receive our full Daily Briefing and support our independent journalism on Mozambique, please do subscribe. And bear in mind our rates are due to rise, for the first time in a long time, at the end of this month — so be quick to lock in the current prices.

Have a great week ahead.

Week in Review

Monday

Back in 2019, the government reached a deal with creditors to swap the bond issued by state-owned company Ematum as part of the larger $2bn debts scheme. As well as being illegally agreed, the original debts had been defaulted on, as the projects they were supposedly set up to finance had come to nothing.

Part of that deal was that interest on the replacement bond, still Mozambique's only international sovereign bond, would increase this year from 5% to 9% per year, raising the interest to be paid on the $900m principal from $45m a year to $81m. The last of the smaller repayments was made last week; the next will be a lot bigger.

It didn’t have to be this way. Leaving aside the question of whether Mozambique should be honouring the debt at all, back in 2019 the government originally agreed with creditors to pay a flat 5.75% interest rate, but to pay them extra depending on how much revenue was coming in from the Rovuma Basin liquefied natural gas (LNG) projects. This proposal was abandoned as being too complicated – and/or politically unpalatable to promise gas revenues to creditors.

Zitamar News called it a mistake back in 2019; that call seems vindicated today.

Tuesday

After weeks during which exporters have received confusing mixed messages from different parts of the authorities, the Ministry of Industry and Commerce has finally confirmed this week that there is no cap on pigeon pea exports - although their excuse, that they needed confirmation from the Indian side, is unbelievable, since Indian diplomats have repeatedly said on the record that there were no limits on pigeon pea exports. In fact, a notice from the Administrative Court last week that it had received a request to overturn the ICM’s decisions seems to have forced the ministry’s hand.

The situation has been exacerbated by the fact that the local port for exporting pigeon peas is the port of Nacala in Nampula, which is a byword for corruption not just in Mozambique but among informed observers across the world. It is hard to expect fair and non-discriminatory treatment from the customs authorities, when smuggling and bribery are the norm.

Wednesday

The UK’s Supreme Court has ruled that the Mozambican government is able to sue shipbuilding firm Privinvest, as part of a trial which is due to begin in London in a few weeks. Mozambique is suing Privinvest over government-guaranteed loans raised as part of the so-called “hidden debts” or tuna bond scandal, and the government’s lawyers say that the state was the victim of a conspiracy by Privinvest which paid bribes and kickbacks to officials and bankers to secure the contracts financed by the loans. Privinvest denies that its payments were bribes, and sought to argue that any such claim against it had to be dealt with through arbitration, not the courts. The Court of Appeal ruled in favour of Privinvest on this point, but the Supreme Court has now overturned that ruling.

The trial due to begin soon will therefore include Mozambique’s claims against Privinvest, which will allow it to argue that the government guarantee on the $622m loan borrowed by state-owned company ProIndicus should be cancelled, and that Privinvest should pay damages to the state. This will include consideration of whether the payments Privinvest made — including payments to President Filipe Nyusi — were bribes. Together with the recent ruling by the High Court in London that Nyusi himself was immune from being made a party to the case, recent court rulings in London have been going against Privinvest.

Thursday

Finance minister Max Tonela is one of president Nyusi's key lieutenants, and there are those in and around government who are seeking to weaken Nyusi and his closest allies.

Tonela was absent from the Council of Ministers on the day that announcement was made; his young deputy was, we understand, unable to make the case for the ministry, that financing was on track, and no ceiling was being hit.

Suaze's announcement caused some panic, but the proof of the pudding is in the eating — and Mozambique's financial markets still have an appetite for government bonds. Like in the US, the question of a debt ceiling has been used for partisan political ends; just in Mozambique, those fights don't happen between two parties, but within the one dominant one: Frelimo.

Friday

The Mozambican government is demanding $10bn in compensation from shipbuilder Privinvest in its litigation with the firm in the High Court in London, newspaper Notícias reports, citing a source in the public prosecutor’s office. The money claimed is for the damage caused by the state-guaranteed loans borrowed by companies to finance a maritime security project as part of the so-called “hidden debts” scandal. The state is also asking the court to declare invalid the sovereign guarantees given in 2013 and 2014, for the loans which totalled around $2bn.

The figure resembles the $11bn which pressure group the Centre for Public Integrity suggested in 2021 was the cost to date of the debts illegally raised by the state to finance Privinvest’s contracts, which the current government claims were obtained through corruption. The debts quickly became unsustainable and they caused Mozambique to lose aid from foreign financiers, on the grounds that the state had deceived them about its finances. This in turn destabilised the economy. The number includes the wider economic damage caused after the existence of the debts came to light, including the cutting off of aid, the devaluation of the currency and the fall in the country’s GDP.