On 24 November, the Constitutional Council, a court with the final say on election results in Mozambique, announced the final version of results in the local elections held on 11 October. The council’s announcement reinforced the perception that it was biased in favour of ruling party Frelimo.

Contrary to the results previously announced by the National Elections Commission (CNE), however, which said that Frelimo had won 64 out of 65 municipalities, the council overturned results in four towns and cities (Chiure, Quelimane, Alto Molócue and Vilankulo) to declare opposition party Renamo a winner there. Frelimo was declared the winner in another 56 municipalities, and the Democratic Movement of Mozambique party’s victory in Beira was upheld. Repeat elections were ordered in four towns (see below).

The most major oversight by the council was its upholding of Frelimo’s supposed victory in Maputo and Matola, Mozambique’s capital city and largest city respectively, despite election observers reporting that Renamo actually got more votes there. The council did transfer some votes from Frelimo to Renamo in the cities (without explaining why), but not enough to change the result.

The council made little reference to irregularities during the voting and vote counting process, or in the elections as a whole, saying that those issues did not influence the overall results. A Supreme Court judge questioned the council’s idea that local courts did not have the power to rule on election matters, sparking a discussion among commentators that the election process needed reform.

According to sources in the political parties, the results presented by the council are understood to be a result of compromise, at least between the leadership of Renamo — a party that originally claimed victory in 21 municipalities — and Frelimo.

As such, it is hard to avoid the conclusion that the decision of the Constitutional Council (several of whose judges are appointed by the president and by members of the Frelimo-dominated parliament) was heavily influenced by Frelimo’s wishes.

From a voter’s perspective, it was a common complaint that the election results took too long to be announced, casting suspicion over the entire process.

Were the elections free and fair?

In a word, no.

Prior to election day, observer groups warned of manipulation to prevent voter registration in opposition strongholds, bussing in Frelimo supporters to register in areas where they did not live, and inflating voter numbers, tainting the integrity of the elections.

Abundant evidence from election day, including ballot stuffing, intimidation of observers, and opposition party representatives at polling stations being chased by police, led many to believe these were the least democratic elections since Mozambique began holding multi-party elections in 1994.

Parallel counts of the vote organised by opposition parties and election observer groups found that in several towns and cities, opposition parties got the most votes, even though Frelimo was officially declared the winner.

There was also evidence of results sheets (editais) being changed by polling station authorities, while in the immediate aftermath of the count, the heads of polling stations in some cases disappeared suddenly, leaving the editais without having signed off on them.

How did Frelimo respond to the election results? How will the results affect Frelimo?

Frelimo originally accepted the official results announced by CNE previously declaring it the winner in 64 out of municipalities, dismissing evidence of malpractice in its favour and saying it relied on the courts to safeguard the vote. However, some within the party have voiced concern over what they said was opposing the popular will, including Samora Machel junior and his step-mother Graça Machel, both related to independent Mozambique’s first president. Frelimo has historically managed dissent in an authoritarian manner, and those interventions have not had any effect on its overall stance.

The party will remain in a dominant position in Mozambique’s politics, as it controls all the machinery of government and public institutions, and it uses public funds to give it an advantage in elections.

It remains to be seen how these results will impact internal dynamics within Frelimo in the run-up to presidential elections next year. President Filipe Nyusi is seen to favour agriculture minister Celso Correia to succeed him as party leader, and therefore Mozambique’s next president. However, the fact that some of Frelimo’s victories were overturned, albeit in relatively small towns and cities, has probably damaged Correia’s standing, since he managed Frelimo’s election campaign. Rivals for the leadership will seek to take advantage.

How did Mozambique’s opposition respond to the election results?

Unlike in previous elections, and despite accusations that courts in the past always found excuses to rule against the opposition, it seems Mozambique’s opposition parties Renamo and the MDM, as well as new entrant New Democracy, were well prepared to make legal challenges to the results. They had more representatives at polling stations, and managed to produce parallel counts and have much better prepared lawyers to file complaints on time. They have also been better prepared to address the media and be present on social networking platforms.

Perhaps the most significant event beyond the results themselves, have been the protests that Renamo called even before the preliminary results were announced, gathering large crowds, notably in Maputo.

In some places protests turned violent, with police firing live ammunition and even killing some protesters. More than a hundred protesters were jailed, though many were promptly released.

In terms of winning power, these elections were a failure for Renamo and the MDM. Nevertheless, Renamo especially improved in popularity, including in traditional Frelimo strongholds. The marches are also an indicator, among other factors, of the extent of their quest to position themselves as a political force rather than the guerrillas of the past. But while Ossufo Momade, the president of the party, said the party would not resort to war to contest election results, and the party would pursue its interests legally, others have taken a more confrontational tone, such as Venâncio Mondlane, Renamo’s popular mayoral candidate in Maputo, António Muchanga, the candidate in Matola, and Manuel Araujo, the mayor of Quelimane.

The contrast in leadership styles and popularity is clear. Momade succeeded the late Afonso Dhlakama and lacks the charisma of the latter. A highly ranked guerrilla fighter during the civil war, who signed the peace deal that led to the current demilitarisation and integration process in 2019, Momade’s leadership has been repeatedly challenged by members of the party and does not seem to resonate with urban or younger members, or potential voters. Many voices are advocating for the party to consider changing its leader.

MDM’s win in Beira proved once again its unquestionable popularity there. Elsewhere, the party did not win a sizable proportion of the vote.

There has been an interesting dynamic amongst the two parties. The hesitation to form a coalition before elections seemed to be a tale from the past, and recently the two parties have acted collaboratively in court battles.

How have the local elections changed Mozambique’s politics?

In the absence of formal opinion polls, perhaps listening to what people said can give a sense of what’s to come. An adolescent, almost certainly below voting age, walking in central Maputo among armoured cars and a strong police presence in the streets in Maputo, said loudly: “We are tired”. However, voting tendencies and protests were driven more by an anti-Frelimo and anti-government policy sentiment (for example, due to problems in paying public servants) than growing popularity for Renamo.

There is a strong feeling among youth that electoral institutions were not reliable and their voices were not heard. Many said they would rather not vote in future since their choice is not respected. This sentiment has the potential to fuel resentment.

Confidence in the electoral authorities - the CNE and the Technical Secretariat for Electoral Administration - has been shaken. In particular, the position of the CNE’s president, Anglican bishop Carlos Matsinhe, has come under attack, with Anglican bishops in Mozambique calling for his resignation.

One can make the case that Frelimo’s legitimacy as a ruling party is shaky, perhaps more than ever before. On the other hand, its grip on public institutions obviously remains largely strong, as borne out by the fact that the electoral authorities and the Constitutional Council basically gave it the result it wanted. Only a few lower courts exercised independence. Frelimo thus looks unlikely to lose power anytime soon, especially if it arranges for the vote to be manipulated again at next year’s general election.

What happened with the repeat elections?

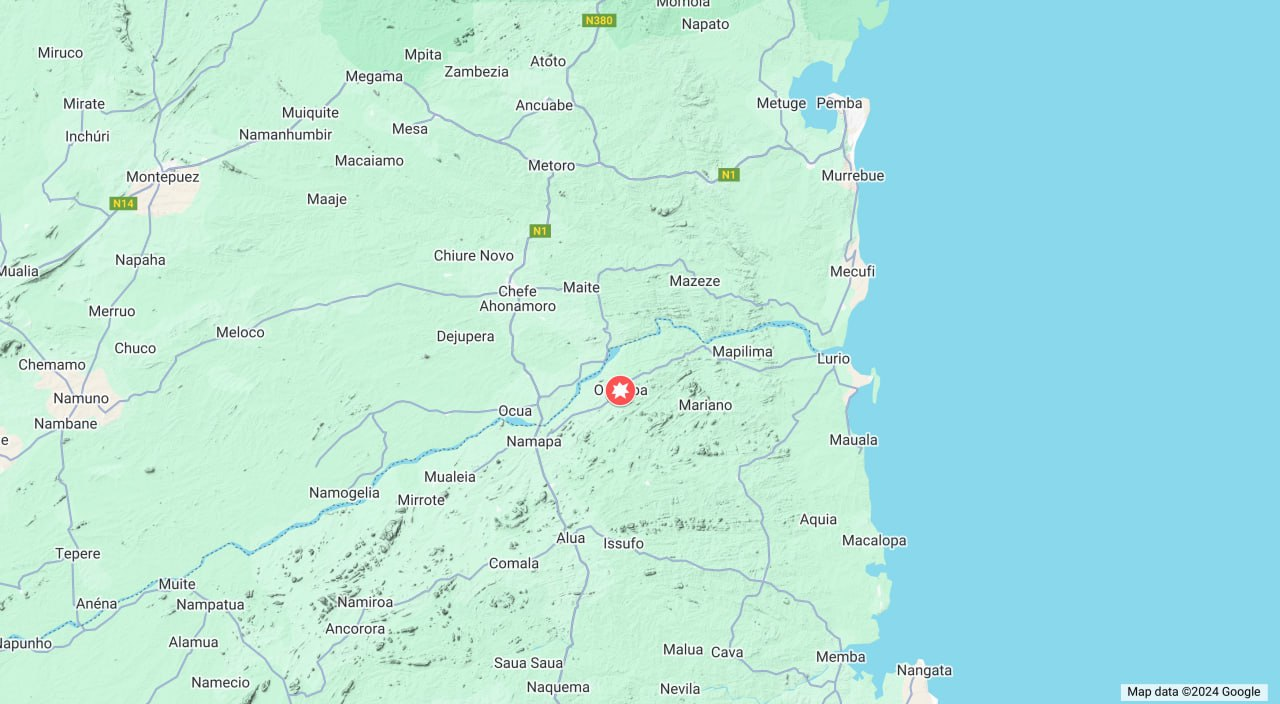

As part of its ruling last month, the Constitutional Council ordered fresh elections to be held in four towns: Marromeu, Nacala-Porto, Gurué and Milange. The entire election was to be re-run in Marromeu and in part (at selected polling stations) in the other three. The repeat elections were held on Sunday 10 December.

In general, and despite electoral authorities promising that anyone found guilty of illegal behaviour in the October election would be removed from running the new elections, fraud and malpractice was observed once again (see roundup of media coverage here). The district election commissions quickly announced that Frelimo had won the elections in all four towns, although a parallel vote count by electoral observers in Marromeu indicated that opposition party Renamo got the most votes there. Renamo has rejected the official result for Marromeu. Ballot-stuffing, the use of ineligible voters and intimidation of election observers was also witnessed. The New Democracy party has filed a legal complaint over the results in Gurué.

A man was shot dead by police in the market area of Marromeu on Tuesday, while police were dealing with a demonstration being held to protest against the disputed election results there. The officer accused of firing the shot is currently in custody, after initially being arrested and then released.